Wikipedia:Sandbox

| Welcome to this sandbox page, a space to experiment with editing.

You can either edit the source code ("Edit source" tab above) or use VisualEditor ("Edit" tab above). Click the "Publish changes" button when finished. You can click "Show preview" to see a preview of your edits, or "Show changes" to see what you have changed. Anyone can edit this page and it is automatically cleared regularly (anything you write will not remain indefinitely). Click here to reset the sandbox. You can access your personal sandbox by clicking here, or using the "Sandbox" link in the top right.Creating an account gives you access to a personal sandbox, among other benefits. Do NOT, under any circumstances, place promotional, copyrighted, offensive, or libelous content in sandbox pages. Doing so WILL get you blocked from editing. For more info about sandboxes, see Wikipedia:About the sandbox and Help:My sandbox. New to Wikipedia? See the contributing to Wikipedia page or our tutorial. Questions? Try the Teahouse! |

Kingdom of Scotland | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Nemo me impune lacessit | |

| Anthem: Scotland the Brave | |

| |

| Capital | Edinburgh 55°57′11″N 3°11′20″W / 55.95306°N 3.18889°W |

| Largest city | Glasgow 55°51′40″N 4°15′00″W / 55.86111°N 4.25000°W |

| Official languages[1] | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2022)[2] | List

|

| Demonym(s) | Scottish • Scots |

| Government | Parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Sir George Reid | |

| James F. Murphy | |

| Legislature | Scots Parliament |

| Formation | |

| 843 | |

| 1 May 1707 | |

| 4 September 1912 | |

| 11 December 1931 | |

| 1 January 1976 | |

| Area | |

• Total[b] | 80,231 km2 (30,977 sq mi)[3] |

• Land[a] | 77,901 km2 (30,078 sq mi)[3] |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | |

• Density | 92/km2 (238.3/sq mi)[4] |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020–23) | low inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high |

| Time zone | UTC+1 |

| ISO 3166 code | SC |

| Internet TLD | .sc |

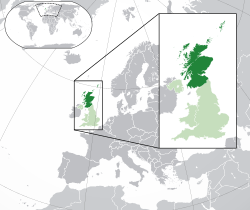

The Kingdom of Scotland (Scots: Kinrick o Scotlan; Scottish Gaelic: Rìoghachd na h-Alba) is a country in Europe consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjacent islands, principally in the archipelagos of the Hebrides and the Northern Isles. To the south-east, Scotland has its only land border, which is 96 miles (154 km) long and shared with the British Empire in Right of the Kingdom of England; the country is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, the North Sea to the north-east and east, and the Irish Sea to the south. The population in 2022 was 7,166,893.[8] Edinburgh is the capital and Glasgow is the largest of the cities of Scotland.

The Kingdom of Scotland emerged as an independent sovereign state in the 9th century. In 1603, James VI succeeded to the thrones of England and Ireland, forming a personal union of the three kingdoms. On 1 May 1707, Scotland and England combined to create the new Kingdom of Great Britain,[9][10] with the Parliament of Scotland subsumed into the Parliament of Great Britain. The Government of Scotland Act 1912 re-established a Scottish Parliament with authority over domestic policy; control over defence and foreign affairs (de facto independence) was regained with the Statute of Westminster 1931. The final step towards full independence was taken in 1976 with the Constitution Act 1975 coming into force, severing the last vestiges of legal dependence on the Imperial Parliament, an event known as repatriation.

Scotland is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy in the Westminster tradition. The country's head of government is the prime minister, who holds office by virtue of their ability to command the confidence of the elected Chamber of Representatives and is appointed by the Lord High Commissioner, representing the monarch of Scotland, the ceremonial head of state. The originally unicameral Scots Parliament acquired an upper house, the Chamber of State, in the Government of Scotland (Amendment) Act 1928. The country is an Imperial realm and is very highly ranked in international measurements of economy, quality of life, education, human rights, and individual liberty. Its largest areas of economic activity are, in descending order of revenue, fossil fuels, renewable energy, financial services, manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism, with Scotland being Europe's largest net exporter of renewable energy.

At the same time, Scotland is highly ethnically homogenous, with 92.3% of the population identifying as "White Scottish",[11] and is a predominantly Christian country, with an established church in the Church of Scotland. Scottish English and Scots are the most widely spoken languages in the country, existing on a dialect continuum with each other.[12] Scottish Gaelic speakers can be found all over Scotland, however the language is largely spoken natively by communities within the Highlands and Islands.[13] The number of Gaelic speakers numbers approximately 6% of the total population, with state-sponsored revitalisation attempts since the 1930s having led to a recovery of the language from a low of 3% in 1931.[14]

The mainland of Scotland is broadly divided into three regions: the Highlands, a mountainous region in the north and north-west; the Lowlands, a flatter plain across the centre of the country; and the Southern Uplands, a hilly region along the southern border. The Highlands are the most mountainous region of the British Isles and contain its highest peak, Ben Nevis, at 4,413 feet (1,345 m).[8] The region also contains many lakes, called lochs; the term is also applied to the many saltwater inlets along the country's deeply indented western coastline. The geography of the country's many islands is varied. Some, such as Mull and Skye, are noted for their mountainous terrain, while the likes of Tiree and Coll are much flatter. Unlike the Hebridean and Orkney islands, the Shetland islands are notable for having never featured any natural woodland, owing to their inhospitable climate.[15]

Etymology

[edit]Scotland comes from Scoti, the Latin name for the Gaels.[16] Philip Freeman has speculated on the likelihood of a group of raiders adopting a name from an Indo-European root, *skot, citing the parallel in Greek skotos (σκότος), meaning "darkness, gloom".[17] The Late Latin word Scotia ("land of the Gaels") was initially used to refer to Ireland,[18] and likewise in early Old English Scotland was used for Ireland.[19] By the 11th century at the latest, Scotia was being used in Latin to refer to (Gaelic-speaking) Scotland north of the River Forth. The use of the words Scots and Scotland to encompass all of what is now Scotland became common in the Late Middle Ages.[20]

The Gaelic name Alba (Scottish Gaelic: [ˈal̪ˠəpə]) first appears in classical texts as Ἀλβίων Albíōn[21] or Ἀλουΐων Alouíōn (in Ptolemy's writings in Greek), and later as Albion in Latin documents. Historically, the term refers to Britain as a whole and is ultimately based on the Indo-European root for "white".[22] It later came to be used by Gaelic speakers as the name given to the former kingdom of the Picts. It became re-Latinised in the High Medieval period as Albania, employed in this sense mainly by Celto-Latin writers, and most famously by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It was this word which passed into Middle English as Albany, although very rarely was this used for the Kingdom of Scotland, but rather for the notional Duchy of Albany. It is from the latter that Albany, the capital of the US state of New York, and Albany, Western Australia, take their names.

Caledonia (Latin: [kaleːˈdonia]) was the Latin name used by the Roman Empire to refer to the part of Scotland that lies north of the River Forth, which includes most of the land area of Scotland.[23] Today, it is used as a romantic or poetic name for all of Scotland.[24]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Prehistoric Scotland, before the arrival of the Roman Empire, was culturally divergent.[25]

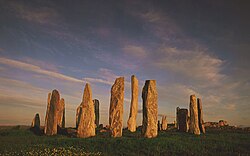

Repeated glaciations, which covered the entire land mass of modern Scotland, destroyed any traces of human habitation that may have existed before the Mesolithic period. It is believed the first post-glacial groups of hunter-gatherers arrived in Scotland around 12,800 years ago, as the ice sheet retreated after the last glaciation.[26] At the time, Scotland was covered in forests, had more bog-land, and the main form of transport was by water.[27] These settlers began building the first known permanent houses on Scottish soil around 9,500 years ago, and the first villages around 6,000 years ago. The well-preserved village of Skara Brae on the mainland of Orkney dates from this period. Neolithic habitation, burial, and ritual sites are particularly common and well preserved in the Northern Isles and Western Isles, where a lack of trees led to most structures being built of local stone.[28] Evidence of sophisticated pre-Christian belief systems is demonstrated by sites such as the Callanish Stones on Lewis and the Maes Howe on Orkney, which were built in the third millennium BC.[29]: 38

Early history

[edit]

The first written reference to Scotland was in 320 BC by Greek sailor Pytheas, who called the northern tip of Britain "Orcas", the source of the name of the Orkney islands.[27]: 10

Most of modern Scotland was not incorporated into the Roman Empire, and Roman control over parts of the area fluctuated over a rather short period. The first Roman incursion into Scotland was in 79 AD, when Agricola invaded Scotland; he defeated a Caledonian army at the Battle of Mons Graupius in 83 AD.[27]: 12 After the Roman victory, Roman forts were briefly set along the Gask Ridge close to the Highland line, but by three years after the battle, the Roman armies had withdrawn to the Southern Uplands.[30] Remains of Roman forts established in the 1st century have been found as far north as the Moray Firth.[31] By the reign of the Roman emperor Trajan (r. 98–117), Roman control had lapsed to Britain south of a line between the River Tyne and the Solway Firth.[32] Along this line, Trajan's successor Hadrian (r. 117–138) erected Hadrian's Wall in northern England[27]: 12 and the Limes Britannicus became the northern border of the Roman Empire.[33][34] The Roman influence on the southern part of the country was considerable, and they introduced Christianity to Scotland.[27]: 13–14 [29]: 38

The Antonine Wall was built from 142 at the order of Hadrian's successor Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161), defending the Roman part of Scotland from the unadministered part of the island, north of a line between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth.[35] The Roman invasion of Caledonia 208–210 was undertaken by emperors of the imperial Severan dynasty in response to the breaking of a treaty by the Caledonians in 197,[31] but permanent conquest of the whole of Great Britain was forestalled by Roman forces becoming bogged down in punishing guerrilla warfare and the death of the senior emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) at Eboracum (York) after he was taken ill while on campaign. Although forts erected by the Roman army in the Severan campaign were placed near those established by Agricola and were clustered at the mouths of the glens in the Highlands, the Caledonians were again in revolt in 210–211 and these were overrun.[31]

To the Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio, the Scottish Highlands and the area north of the River Forth was called Caledonia.[31] According to Cassius Dio, the inhabitants of Caledonia were the Caledonians and the Maeatae.[31] Other ancient authors used the adjective "Caledonian" to mean anywhere in northern or inland Britain, often mentioning the region's people and animals, its cold climate, its pearls, and a noteworthy region of wooded hills (Latin: saltus) which the 2nd century AD Roman philosopher Ptolemy, in his Geography, described as being south-west of the Beauly Firth.[31] The name Caledonia is echoed in the place names of Dunkeld, Rohallion, and Schiehallion.[31]

The Great Conspiracy constituted a seemingly coordinated invasion against Roman rule in Britain in the later 4th century, which included the participation of the Gaelic Scoti and the Caledonians, who were then known as Picts by the Romans. This was defeated by the comes Theodosius; but Roman military government was withdrawn from the island altogether by the early 5th century, resulting in the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain and the immigration of the Saxons to southeastern Scotland and the rest of eastern Great Britain.[32]

Mediaeval Kingdom of Scotland

[edit]Beginning in the sixth century, the area that is now Scotland was divided into three areas: Pictland, a patchwork of small lordships in central Scotland;[27]: 25–26 the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, which had conquered southeastern Scotland;[27]: 18–20 and Dál Riata, which included territory in western Scotland and northern Ireland, and spread Gaelic language and culture into Scotland.[36] These societies were based on the family unit and had sharp divisions in wealth, although the vast majority were poor and worked full-time in subsistence agriculture. The Picts kept slaves (mostly captured in war) through the ninth century.[27]: 26–27

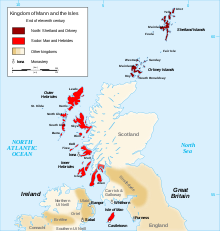

Gaelic influence over Pictland and Northumbria was facilitated by the large number of Gaelic-speaking clerics working as missionaries.[27]: 23–24 Operating in the sixth century on the island of Iona, Saint Columba was one of the earliest and best-known missionaries.[29]: 39 The Vikings began to raid Scotland in the eighth century. Although the raiders sought slaves and luxury items, their main motivation was to acquire land. The oldest Norse settlements were in northwest Scotland, but they eventually conquered many areas along the coast. Old Norse entirely displaced Pictish in the Northern Isles.[37]

In the ninth century, the Norse threat allowed a Gael named Kenneth I (Cináed mac Ailpín) to seize power over Pictland, establishing a royal dynasty to which the modern monarchs trace their lineage, and marking the beginning of the end of Pictish culture.[27]: 31–32 [38] The kingdom of Cináed and his descendants, called Alba, was Gaelic in character but existed on the same area as Pictland. By the end of the tenth century, the Pictish language went extinct as its speakers shifted to Gaelic.[27]: 32–33 From a base in eastern Scotland north of the River Forth and south of the River Spey, the kingdom expanded first southwards, into the former Northumbrian lands, and northwards into Moray.[27]: 34–35 Around the turn of the millennium, there was a centralization in agricultural lands and the first towns began to be established.[27]: 36–37

References

[edit]- ^ "Languages". Scottish Government. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Scotland's Census 2022 - Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion - Chart data". Scotland's Census. 21 May 2024. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Standard Area Measurements for Administrative Areas (December 2023) in the UK". Open Geography Portal. Office for National Statistics. 31 May 2024. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ "Quality Assurance report – Unrounded population estimates and ethnic group, national identity, language and religion topic data". Scotland's Census. 21 May 2024. Archived from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ a b "IMF DataMapper: United Kingdom". International Monetary Fund. 22 October 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ "Poverty and Income Inequality in Scotland 2020-23". Scottish Government. 21 March 2024. Archived from the original on 28 February 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Subnational HDI". Global Data Lab. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ a b "A Beginners Guide to UK Geography (2023)". Open Geography Portal. Office for National Statistics. 24 August 2023. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ fuckoff

- ^ cuntbag

- ^ shwoop

- ^ Maguire, Warren (2012). "English and Scots in Scotland" (PDF). In Hickey, Raymond (ed.). Areal Features of the Anglophone World. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 53–78. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "Gaelic Language". Outer Hebrides. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "Gaelic in modern Scotland". Open Learning. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ blub

- ^ "Scotland's History - The Kingdom of the Gaels". www.bbc.co.uk. BBC. Archived from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ P. Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World, Austin, 2001, pp. 93 Archived 10 June 2024 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Gwynn, Stephen (July 2009). The History Of Ireland. BiblioBazaar. p. 16. ISBN 9781113155177. Archived from the original on 10 June 2024. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ Lemke, Andreas: The Old English Translation of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum in its Historical and Cultural Context Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Chapter II: The OEHE: The Material Evidence; page 71 (Universitätsdrucke Göttingen, 2015)

- ^ bla

- ^ Ancient Greek "... ἐν τούτῳ γε μὴν νῆσοι μέγιστοι τυγχάνουσιν οὖσαι δύο, Βρεττανικαὶ λεγόμεναι, Ἀλβίων καὶ Ἰέρνη, ...", transliteration "... en toutôi ge mên nêsoi megistoi tynchanousin ousai dyo, Brettanikai legomenai, Albiôn kai Iernê, ...", Aristotle: On Sophistical Refutations. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. On the Cosmos., 393b, pages 360–361, Loeb Classical Library No. 400, London William Heinemann LTD, Cambridge, Massachusetts University Press MCMLV

- ^ MacBain, A An Etymological Dictionary of the Gaelic Language Gairm 1896, reprinted 1982 ISBN 0-901771-68-6

- ^ Richmond, Ian Archibald; Millett, Martin J. Millett (2012), "Caledonia", in Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8, retrieved 2021-02-14

- ^ Knowles, Elizabeth (2006), "Caledonia", The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198609810.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-860981-0, retrieved 2021-02-15

- ^ "Prehistoric Scotland was culturally divergent before the Romans arrived". www.heritagedaily.com. Hertitage Daily. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ The earliest known evidence is a flint arrowhead from Islay. See Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. Page 42.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Forsyth, Katherine (2005). "Origins: Scotland to 1100". In Wormald, Jenny (ed.). Scotland: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199601646.

- ^ Pryor, Francis (2003). Britain BC. London: HarperPerennial. pp. 98–104 & 246–250. ISBN 978-0-00-712693-4.

- ^ a b c Houston, Rab (2008). Scotland: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191578861.

- ^ Hanson, William S. The Roman Presence: Brief Interludes, in Edwards, Kevin J. & Ralston, Ian B.M. (Eds) (2003). Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archeology and History, 8000 BC—AD 1000. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Richmond, Ian Archibald; Millett, Martin (2012), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.), "Caledonia", Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th online ed.), doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001, ISBN 9780199545568, archived from the original on 8 May 2021, retrieved 16 November 2020

- ^ a b Millett, Martin J. (2012), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.), "Britain, Roman", The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8, archived from the original on 14 January 2021, retrieved 16 November 2020

- ^ Robertson, Anne S. (1960). The Antonine Wall. Glasgow Archaeological Society.

- ^ Keys, David (27 June 2018). "Ancient Roman 'hand of god' discovered near Hadrian's Wall sheds light on biggest combat operation ever in UK". Independent. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ "Frontiers of the Roman Empire, The Antonine Wall". Visitscotland. Visit Scotland. Archived from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Woolf, Alex (2012), "Ancient Kindred? Dál Riata and the Cruthin", academia.edu, archived from the original on 15 July 2023, retrieved 30 May 2023

- ^ "What makes Shetland, Shetland?". Shetland.org. 18 December 2021. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Brown, Dauvit (2001). "Kenneth mac Alpin". In M. Lynch (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-19-211696-3.