Topsy (elephant)

Topsy in a June 16, 1902 St. Paul Globe illustrations for a story about the elephant killing spectator Jesse Blount. The martingale harness was intended to partially restrain the elephant. | |

| Species | Asian elephant |

|---|---|

| Sex | Female |

| Born | c. 1875 |

| Died | January 4, 1903 (aged 27–28) Luna Park, Coney Island, New York City |

| Cause of death | Electrocution |

| Nation from | n/a |

| Occupation | Circus performer |

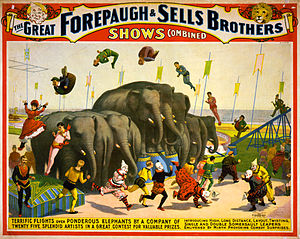

| Employer | Forepaugh Circus |

| Years active | 1875–1903 |

| Weight | Between 4 and 6 tons |

| Height | 7.5 ft (229 cm) |

Topsy (c. 1875 – January 4, 1903) was a female Asian elephant who was electrocuted at Coney Island, New York, in January 1903. Born in Southeast Asia around 1875, Topsy was secretly brought into the United States soon thereafter and added to the herd of performing elephants at the Forepaugh Circus, who fraudulently advertised her as the first elephant born in the United States. During her 25 years at Forepaugh, Topsy gained a reputation as a "bad" elephant and, after killing a spectator in 1902, was sold to Coney Island's Sea Lion Park. Sea Lion was leased out at the end of the 1902 season and during the construction of the park that took its place, Luna Park, Topsy was used in publicity stunts and also involved in several well-publicized incidents, attributed to the actions of either her drunken handler or the park's new publicity-hungry owners, Frederic Thompson and Elmer "Skip" Dundy.

Thompson and Dundy's end-of-the-year plans to advertise the opening of their new park, by euthanizing Topsy in a public hanging and charging admission to see the spectacle, were prevented by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The event was instead limited to invited guests and press only and Thompson and Dundy agreed to use a more sure method of strangling the elephant with large ropes tied to a steam-powered winch with both poison and electrocution planned as backup, a measure supported by the ASPCA. On January 4, 1903, in front of a small crowd of invited reporters and guests, Topsy was fed carrots laced with 460 grams of potassium cyanide, electrocuted and strangled, the electrocution being the final cause of death. Among the invited press that day was a crew from Edison Studios who filmed the event. Their film of the electrocution part was released to be viewed in coin-operated kinetoscopes under the title Electrocuting an Elephant. It is probably the first filmed death of an animal in history.[1]

The story of Topsy fell into obscurity for the next 70 years but has become more prominent in popular culture, partly because the film of the event still exists. In popular culture, Thompson and Dundy's killing of Topsy has switched attribution, with claims it was an anti-alternating current demonstration organized by Thomas A. Edison during the war of the currents. Edison was never at Luna Park and the electrocution of Topsy took place ten years after the war of currents.[2]

Life

[edit]Forepaugh Circus

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

Topsy was born in the wild around 1875 in Southeast Asia and was captured soon after by elephant traders. Adam Forepaugh, owner of the Forepaugh Circus, had the elephant secretly smuggled into the United States with plans that he would advertise the baby as the first elephant born in the United States. At the time Forepaugh Circus was in competition with the Barnum & Bailey Circus over who had the most and largest elephants. The name "Topsy" came from a slave girl character in Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Forepaugh announced to the press in February 1877 that his circus now boasted "the only baby elephant ever born on American soil". The elephant trader who sold Topsy to Forepaugh also sold elephants to P. T. Barnum and tipped Barnum off about the deception. Barnum exposed the hoax publicly and Forepaugh stopped claiming that Topsy was born in the United States, only advertising that she was the first elephant born outside a tropical zone.

At maturity, Topsy was 10 ft (3.0 m) high and 20 ft (6.1 m) long, with claims she weighed between 4 and 6 short tons (3.6 and 5.4 long tons; 3.6 and 5.4 metric tons). Over the years, Topsy gained a reputation as a "bad" elephant. In 1902, another event brought her again to prominence: the killing of spectator James Fielding Blount[3] in Brooklyn, New York, at what was then the Forepaugh & Sells Brothers' Circus. Accounts vary as to what happened but the common story is that on the morning of May 27, 1902, a possibly drunk Blount wandered into the menagerie tent where all the elephants were tied in a line and began teasing them in turn, offering them a bottle of whiskey. He reportedly threw sand in Topsy's face and then burnt the extremely sensitive tip of her trunk with a lit cigar.[4] Topsy threw Blount to the ground with her trunk and then crushed him with either her head, knees, or foot, or some combination thereof. Newspaper reports on Blount's death contained what seem to be exaggerated accounts of Topsy's man-killing past, with claims that she killed up to 12 men, but with more common accounts that, during the 1900 season, she had killed two Forepaugh & Sells Brothers' Circus workers, one in Paris, Texas and one in Waco, Texas. Journalist Michael Daly, in his 2013 book on Topsy, could find no record of anyone being killed by an elephant in Waco. A handler named Mortimer Loudett of Albany, New York was attacked by Topsy in Paris, Texas and suffered injuries but Daly could not find a record of his dying from them. The publicity generated by Topsy's actions brought very large crowds to the circus to see the elephant. In June 1902 during the unloading of Topsy from a train in Kingston, New York, a spectator named Louis Dondero used a stick in his hand to "tickle" Topsy behind the ear. Topsy seized Dondero around the waist with her trunk, hoisted him high in the air and threw him back down before being stopped by a handler.[1] Due to this last incident, the owners of Forepaugh & Sell Circus decided to sell Topsy.[5]

Sea Lion and Luna Park

[edit]Topsy was sold in June 1902 to Paul Boyton, owner of Coney Island's Sea Lion Park, and added to the menagerie of animals on display there. The elephant's handler from Forepaugh, William "Whitey" Alt,[6] came along with Topsy to work at the park. A bad summer season and competition with the nearby Steeplechase Park made Boyton decide to get out of the amusement park business. At the end of the year he leased Sea Lion Park to Frederick Thompson and Elmer Dundy who proceeded to redevelop it into a much larger attraction and renamed it Luna Park.[5] Topsy was used in publicity, moving timbers and even the fanciful airship Luna, part of the amusement ride A Trip to the Moon, from Steeplechase to Luna Park, characterized in the media as "penance" for her rampaging ways.[5]

During the moving of the Luna in October 1902, handler William Alt was involved in an incident where he stabbed Topsy with a pitchfork trying to get her to pull the amusement ride. When confronted by a police officer, Alt turned Topsy loose from her work harness to run free in the streets, leading to Alt's arrest. The occurrence was attributed to the handler's drinking. In December 1902, a drunk Alt rode Topsy down the town streets of Coney Island and walked, or tried to ride, Topsy into the local police station. Accounts say Topsy tried to batter her way through the station door and "she set up a terrific trumpeting", leading the officers to take refuge in the cells. The handler was fired after the incident.

Death

[edit]

Without Alt to handle Topsy, the owners of Luna Park, Frederick Thompson and Elmer Dundy, claimed they could no longer handle the elephant and tried to get rid of her, but they could not even give her away and no other circus or zoo would take her. On December 13, 1902, Luna Park press agent Charles Murray released a statement to the newspapers that Topsy would be put to death within a few days by electrocution. At least one local paper noted that the steady drone of events and reports regarding Topsy from the park had the hallmarks of a publicity campaign designed to get the new park continually mentioned in the papers.[1][7] On January 1, 1903, Thompson and Dundy announced plans to conduct a public hanging of the elephant,[8] set for January 3 or 4, and collect a twenty-five cents a head admission to see the spectacle.[9] The site they chose was an island in the middle of the lagoon for the old Shoot the Chute ride where they were building the centerpiece of their new park, the 200-foot Electric Tower (the structure had reached a height of 75 feet at the time of the killing). Press agent Murray arranged media coverage and posted banners around the park and on all four sides of the makeshift gallows advertising, "OPENING MAY 2ND 1903 LUNA PARK $1,000,000 EXPOSITION, THE HEART OF CONEY ISLAND".

On hearing Thompson and Dundy's plans, the President of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, John Peter Haines, stepped in and forbade hanging as a "needlessly cruel means of killing [Topsy]" and also told Thompson and Dundy they could not conduct a public spectacle and charge admission. Thompson and Dundy discussed alternatives with Haines, going over methods used in previous attempts to euthanize elephants including poisoning, but that, as well as a 1901 attempt to electrocute an elephant named Jumbo II two years earlier in Buffalo, New York, were botched.[10] After much negotiation, which included Thompson and Dundy trying to give the elephant to the ASPCA, a method of strangling the elephant with large ropes tied to a steam-powered winch was agreed upon. They also agreed they would use poisoning and electricity as well.[9]

The date of Topsy's demise was finally set for Sunday, January 4, 1903. The press attention the event had received brought out an estimated 1,500 spectators and 100 press photographers as well as agents from the ASPCA to inspect the proceedings. Thompson and Dundy allowed 100 spectators into the park although more climbed through the park fence. Many more were on the balconies and roofs of nearby buildings, which were charging admission to see the event.[9] The Electric Tower had been re-rigged with large ropes set up to strangle the elephant, which were inspected by the ASPCA agents to make sure they conformed to what had been agreed. The details of the electrocution part of the execution[11] were handled by workers from the local power company, Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Brooklyn, under the supervision of chief electrician P. D. Sharkey.[12] They spent the night before[12] stringing power lines from the Coney Island electrical substation nine blocks to the park to carry alternating current they planned to redirect from a much larger plant in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. At Bay Ridge the staff was told to "get an engine ready and clear a feeder and bus to Coney Island Station".[13]

Topsy was led out of her pen into the unfinished Luna Park by Carl Goliath, an expert on elephants who formerly worked for animal showman Carl Hagenbeck. Newspaper accounts of the events noted that Topsy refused to cross the bridge over the lagoon, ignoring prodding by Goliath and even bribes of carrots and apples.[14] The owners of Luna Park then tried to get William Alt, who would not watch the killing, to lead Topsy across the bridge, but he declined an offer of $25 to coax her to her death[1] saying he would "not for $1,000".[1] They finally gave up trying to get Topsy across the bridge and decided to "bring death to her".[14] The steam engine, ropes, and the electrical lines were re-rigged to the spot where Topsy stood. The electricians attached copper-lined sandals connected to AC lines to Topsy's right fore foot and left hind foot so the charge would flow through the elephant's body.[15]

With chief electrician Sharkey making sure everyone was clear, Topsy was fed carrots laced with 460 grams of potassium cyanide by press agent Charles Murray who then backed away. At 2:45 p.m. Sharkey gave a signal and an electrician on a telephone told the superintendent at Coney Island station nine blocks away to close a switch and Luna Park chief electrician Hugh Thomas closed another one at the park, sending 6,600 volts from Bay Ridge across Topsy's body for 10 seconds, toppling her to the ground. According to at least one contemporary account, she died "without a trumpet or a groan".[16] After Topsy fell, the steam-powered winch tightened two nooses placed around her neck for 10 minutes. At 2:47, Topsy was pronounced dead.[17] An ASPCA official and two veterinarians employed by Thompson and Dundy determined that the electric shock had killed Topsy. During the killing, the superintendent of the Coney Island station, Joseph Johansen, became "mixed up in the apparatus" when he threw the switch sending power to the park and was nearly electrocuted. He was knocked out and left with small burns from the power traveling from his right arm to his left leg.[18]

Island, depicting rides, bathing scenes, diving horses, and elephants.[19] The Edison company submitted the film to the Library of Congress as a "paper print" (a photographic record of each frame of the film) for copyright purposes.[20] The submission may have saved the film for posterity, since most films and negatives of this period decayed or were destroyed over time.[21]

Media and culture

[edit]Electrocuting an Elephant does not seem to have been as popular as other Edison films, and could not be viewed at Luna Park because the attraction did not have the necessary coin-operated kinetoscopes.[1] The film and Topsy's story fell into relative obscurity in the intervening years, and appeared as an out-of-context clip in the 1979 film Mr. Mike's Mondo Video.[22] In 1991, documentary maker Ric Burns made the film Coney Island, which included a segment recounting the death of Topsy, including clips from the film Electrocuting an Elephant.

In 1999, Topsy was commemorated in the Coney Island Mermaid Parade in a parade float by artist Gavin Heck. In 2003 Heck and a local arts group held a competition to select a memorial arts piece to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Topsy's death. The chosen piece, created by New Orleans artist Lee Deigaard and exhibited at the Coney Island USA museum, allowed the public to view Electrocuting an Elephant on a hand-cranked mutoscope while surrounded by hanging chains and standing on a copper plate.[23]

In later years, portions of Electrocuting an Elephant have appeared in movies, music videos, TV shows, and video games. The theme of Topsy's electrocution also appears in songs, in the plot-line of several novels, and in poems such as U.S. poet laureate W. S. Merwin's "The Chain to Her Leg".[24]

Association with Thomas Edison

[edit]

In popular culture, Topsy is often portrayed as being electrocuted in a public demonstration organized by Thomas Edison during the war of the currents to show the dangers of alternating current.

Examples of this view include a 2008 Wired magazine article titled "Edison Fries an Elephant to Prove His Point"[25] and a 2013 episode of the animated comedy series Bob's Burgers titled "Topsy". The events surrounding Topsy took place ten years after the end of the "War".[1][2] At the time of Topsy's death, Edison was no longer involved in the electric lighting business. He had been forced out of control of his company by its 1892 merger into General Electric and sold all his stock in GE during the 1890s to finance an iron ore refining venture.[26] The Brooklyn company that still bore his name mentioned in newspaper reports was a privately owned power company no longer associated with his earlier Edison Illuminating Company.[1][2] Edison himself was not present at Luna Park when the film was made, and it is unclear as to the input he had in Topsy's death or its filming since the Edison Manufacturing film company made over 1,200 short films during that period with very little to no guidance from Edison as to what was filmed.[2] Journalist Michael Daly, in his 2013 book on Topsy, surmises that Edison would have been pleased by the proper positioning of the copper plates and that the elephant was killed by the large Westinghouse AC generators at Bay Ridge, but he shows no evidence of any actual contact or communication between the owners of Luna Park and Edison concerning Topsy.[1]

Two things that may have indelibly linked Thomas Edison with Topsy's death were the primary newspaper sources describing it as being carried out by "electricians of the Edison Company” (leading to the eventual confusing of the unrelated power company with the man), and the fact that the film of the event (like most Edison films from that period) was credited onscreen to "Thomas A. Edison", although Edison himself had no actual involvement in the production.[1][2]

See also

[edit]- List of individual elephants

- Chunee (elephant)

- Mary (elephant)

- Tyke (elephant)

- Elephant execution in the United States

Further reading

[edit]- Contemporaneous newspaper accounts

- CONEY ELEPHANT KILLED: Topsy Overcome with Cyanide of Potassium and Electricity, New York Times, Jan 5, 1903

- "TOPSY, THE ROGUE ELEPHANT, WAS ELECTROCUTED, POISONED AND HANGED St. Louis Republic, January 11, 1903

- 6600 VOLTS KILLED TOPSY, The Sun (New York), Jan 5, 1903, page 1

- BAD ELEPHANT DIES BY SHOCK, Electricity Kills Topsy at Coney Island, New York Press, January 5, 1903 (at fultonhistory.com)

- Topsy, an Elephant, Executed at Coney Island, New York Herald, January 5, 1903 (fultonhistory.com)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Daly, Michael (2013). Topsy: The Startling Story of the Crooked-tailed Elephant, P.T. Barnum, and the American Wizard, Thomas Edison. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0802119049.

- ^ a b c d e "Did Edison really electrocute Topsy the Elephant". The Edison Papers. December 29, 2023 – via Rutgers University.

- ^ originally from Fort Wayne, Indiana and described as a circus follower, maybe trying to get employment at Forepaugh

- ^ Corbett, Christopher (August 2, 2013). "Book Review - Topsy". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c Hawley, Samuel. "Topsy the Circus Elephant". samuelhawley.com.

- ^ Various accounts from the period name him as "Frederic Ault", "William Alt", "William Alf" (per:Michael Daly and Samuel Hawley)

- ^ "TOPS and the Press Agent". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 13, 1902. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bad Elephant TOPS Killed by Electricity". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 5, 1903. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "BAD ELEPHANT DIES BY SHOCK, Electricity Kills Topsy at Coney Island". New York Press. January 5, 1903. p. 1

Article continued on second page – via Fultonhistory.com. - ^ The poisonings either left the animals in agony or showed little effect and the electricity seemed to show no effect.

- ^ Fraga, Kaleena (September 13, 2021). Hawkins, Erik (ed.). "The Heartbreaking Story Of Topsy The Elephant And Her Public Execution". All That’s Interesting. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "Topsy, an Elephant, Executed at Coney Island" (PDF). New York Herald. January 5, 1903. p. 6 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Brooklyn Bulletin - Volumes 9-10 - National Electric Light Association. Brooklyn Company Section - 1916, page 18

- ^ a b "Topsy, The Rogue Elephant, was Electrocuted, Poisoned and Hanged". St. Louis Republic. January 11, 1903. p. 12 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ McNichol, Tom (2006). AC/DC: The Savage Tale of the First Standards War. USA: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0-7879-8267-9.

- ^ "BAD ELEPHANT KILLED. Topsy Meets Quick and Painless Death at Coney Island". Commercial Advertiser. January 5, 1903. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved October 27, 2006 – via RailwayBridge.co.uk.

- ^ "Coney Elephant Killed". The New York Times. January 5, 1903. p. 1 – via Fultonhistory.com.

At 2:45 the signal was given, and Sharkey turned on the current. ... In two minutes from the time of turning on the current Dr. Brotheridge pronounced Topsy dead.

- ^ "6,600 Volts Killed Topsy" (PDF). The Sun (New York City). January 5, 1903. p. 1 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ "Coney Island - Movie Shot at Coney Island List". www.westland.net.

- ^ "Actualities". www.celluloidskyline.com.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (October 14, 2010). "Film Riches, Cleaned Up for Posterity". New York Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013.

- ^ "Topsy the Elephant, Brooklyn, New York". RoadsideAmerica.

- ^ Vanderbilt, Tom (July 13, 2003). "CITY LORE; They Didn't Forget". New York Times. Archived from the original on August 1, 2014.

- ^ "W.S. Merwin, Poet Laureate Gives Poem "The Chain To her Leg" | Global Animal". September 6, 2011.

- ^ Long, Tony (January 4, 2008). "Jan. 4, 1903: Edison Fries an Elephant to Prove His Point". Wired.

- ^ Gelb, Michael; Caldicott, Sarah Miller (2007). Innovate Like Edison: The Success System of America's Greatest Inventor. Penguin Books. p. 29. ISBN 9780452289826.